From iTunes playlists to Facebook profiles, we’re surrounded by metadata every day. But when asked to define “metadata,” most people fall back on “data about data” or talk about database records, library catalogs, and <meta> tags. These are convenient dodges, but talking about structure and use would be more accurate and descriptive, if less pithy. “Preservation metadata” moves us in that direction, but in many ways muddles the waters even more, because it adds another term to the mix that is not well-understood: digital preservation. So what are we actually talking about when we talk about “preservation metadata”? More specifically, how does it fit in among other types of metadata, what does it do, and what does it look like? These turn out to be difficult questions to answer.

Depending on who you talk to, there are three different types of metadata: descriptive, administrative, and structural. Each of these different types are characterized by the purpose or function that they’re intended to serve, whether that’s providing access (descriptive), making it easier to manage collections (administrative), or telling us how complex objects fit together (structural). There is no preservation type. Instead, preservation is a role that any of the above types can play in a particular system. Any metadata that is used to preserve digital objects is preservation metadata, which can include descriptive, administrative, or structural. The first problem, then, is that preservation metadata doesn’t seem to fit anywhere in our neat metadata taxonomy.

Trying to put a finger on preservation metadata is tricky not only because it encompasses so many different types of metadata, but also because we don’t really know exactly what data and how much of it is needed to preserve digital objects. Once a preservation system has been implemented, it might be decades before implementers know whether or not they’ve guessed correctly. Unlike descriptive, administrative, and structural metadata, there’s no way to test the effectiveness of preservation metadata in real-time, which makes it even more difficult to distinguish between the necessary, the optional-if-you’ve-got-the-money, and the total-waste-of-time. For larger libraries, with larger budgets and more staff, it might be easier to plan for the worst and include any information about an object that might be useful, but for smaller and medium sized libraries, it is even more important to balance caution with economic reality. We have to guess even more carefully.

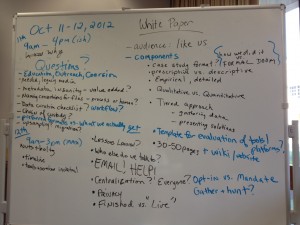

The third problem is one of variety. The OAIS model describes a generic preservation system, and in doing so provides us with the language we need to talk about digital preservation. It even tells us, in broad strokes, what sort of information is typically required to preserve a digital object, including provenance, context, reference, fixity, and access rights. A data model like PREMIS takes us to the next level, defining the core “semantic units” needed to support such a system, but, again, always in the abstract. Neither OAIS nor PREMIS tell us what data needs to be collected or how it should actually be implemented, because those answers vary depending on the system, the preservation strategy, and the format types. Different kinds and different amounts of data will be needed to support emulation than will be needed to support bit-level preservation, and the data needed to describe an image will be vastly different from the data needed to describe a Word file. We can talk about preservation metadata at a higher level, but what that data actually looks like will depend almost entirely on what we’re trying to preserve, how we’re trying to preserve it, and the tools we’re using.

So what is “preservation metadata”? It encompasses many different things, it’s mostly well-informed guesswork, and it comes in a variety of flavors. To follow in Lynne’s tradition of craft metaphors, it’s like a quilt with many different garish patterns that we hope will one day keep us warm. But I might stick with “preservation data about data” for now.